In my youth I saw the American phenomenon as a hero, but before long he began to wobble on his pedestal.

.

I learned about Queen’s Gambit long before the Netflix miniseries of that name became very popular. In 1955, in Hungary, then solidly behind the Iron Curtain, we had chess lessons in class. The Soviets believed that skill at the world’s most popular board game could be used to demonstrate the intellectual superiority of communism. Of course, in grade 3, I didn’t know anything about the Cold War and just enjoyed learning how to play. After coming to Canada, my interest increased because reading chess publications didn’t require knowledge of English.

Announcement 2

.

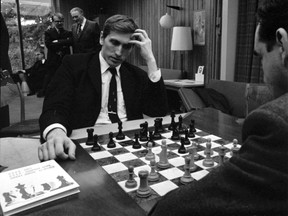

It didn’t take me long to learn the language and soon I was reading about a young phenomenon in the world of chess who had won the United States championship in 1958 at the surprisingly young age of 15. Bobby Fischer would go on to repeat this performance seven more times. I was very amused when I heard that he was coming to Montreal in 1964 to play simultaneously against 56 experts at Sir George Williams University, now Concordia. I was there to see him beat 48 of the opponents, draw with seven and lose with just one. The next day, at the Jewish Public Library, he defeated all 10 opponents in another brilliant display of simultaneous chess. Fischer seemed affable, witty and had a dry sense of humor. I liked

I didn’t hear much more about Fischer until one busy weekend in September 1972, though I later learned that he had appeared on American talk shows criticizing the Soviets for rigging tournaments and had bluntly declared that he was ready to compete for the World Championship. Of chess. Championship. And dare, he did! In the preliminaries, Fischer bested two of the top contenders to earn the right to play then-champion Boris Spassky in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Announcement 3

.

The perspective of this party at the height of the Cold War was presented as an intellectual confrontation between the “communists” and the “free world”. For the first time in history, a chess match would be televised live! Chess fever in the United States skyrocketed. Unfortunately, there was controversy from the start, as Fischer refused to show up in Reykjavik for the opening match unless the prize money was increased. When he finally arrived, after a patriotic appeal from Henry Kissinger, he complained that the spectators were too close and the television cameras were too noisy. He would not play unless the situation was remedied. The organizers finally gave in to the demands and the matches were played in a room without spectators and equipped only with closed circuit cameras.

Announcement 4

.

In what came to be called “The Match of the Century,” Fischer defeated Spassky, ending 24 years of Soviet domination, becoming a hero to Americans and to me as well. I eagerly read the match reports and was elated when Spassky conceded the final game on September 1. My happiness would not last long because the next day I was at the Forum in Montreal to watch Soviet hockey “fans” demolish the Canadian. “professionals” in the first match of another “Match of the Century”.

Having your heroes knocked off a pedestal is very disturbing. While the Canadian pros came back to beat the Soviets in hockey, Bobby Fischer would soon begin to teeter on his pedestal. In 1975, he was supposed to defend his title against young Soviet sensation Anatoly Karpov, but it didn’t happen. This time, the International Chess Federation failed to meet Fischer’s ever-increasing outrageous demands and he was forced to lose the title. He then disappeared from the public eye until 1992 when he came out of seclusion for a rematch with Boris Spassky in Yugoslavia which he won again. However, at the time, the press had been reporting on Fischer’s eccentricities and paranoia. He believed that the televisions gave off dangerous radiation, that the Soviets were trying to poison him and monitoring his activities by reflecting radio signals from his dental fillings. The fillings were removed. Fischer had joined the Worldwide Church of God, whose leader, Herbert Armstrong, prophesied that the world would soon come to an end. When this was not met, Fischer left the church and vigorously attacked it for being “satanic”.

ad 5

.

It was after the 1992 match that Fischer not only figuratively fell off the pedestal, but crashed and burned. The US government had banned doing any kind of business in Yugoslavia due to the war in Bosnia and warned Fischer that if he played Spassky, he would be arrested if he returned to his homeland. As recorded by the television cameras, he spat on the letter, starting a crusade of hatred towards the United States and in particular towards the Jews. Bobby Fischer became a furious anti-Semite, despite the fact that his mother and biological father were Jewish. He also applauded the 9/11 attack on the twin towers in New York.

Banned in the United States, he lived for a time in the Philippines, Hungary, and Japan. In 2004 he was arrested in Japan for trying to leave the country on a revoked US passport. The Icelandic chess community came to his aid by petitioning the Icelandic government to grant him asylum and citizenship, which he did. Fischer lived in Iceland until his death from kidney disease in 2008, retiring from chess but not from his tirades against Jews and the United States. His mental condition has been discussed in the medical literature, but since Fischer never had a formal evaluation by a psychiatrist, only theories have been offered, with paranoid personality disorder being the most prevalent.

ad 6

.

Bobby Fischer died without a will, leaving his American nephews, Japanese wife Miyoko Watai, and Marylin Young, a Filipino woman who claimed Fischer fathered her daughter Jinky, to fight over his estate valued at around $2 million. Iceland agreed to a request by Young to have Fischer’s body exhumed, but analysis of the DNA samples clearly ruled out that Fischer was Jinky’s father. A court found that Miyoko Watai, a pharmacist and president of the Japan Chess Association, had married Fischer in 2004 in Japan and was therefore entitled to inherit his estate.

Bobby Fischer left an enigmatic legacy. He was undoubtedly one of the most brilliant chess players of all time, but his achievements will be forever clouded by his descent into the pit of racist paranoia.

Joe Schwarcz is director of the Office of Science and Society at McGill University (mcgill.ca/oss). He hosts The Dr. Joe Show on CJAD Radio 800 AM every Sunday from 3-4 p.m.

-

The Right Chemistry: Honey Bees, Bananas, and a Solved Mystery

-

The Right Chemistry: The Incendiary Story of Flammable Fabrics