It’s a common story, repeated over and over again: Horses didn’t exist on Turtle Island until European contact, when the Spanish brought them. The animals escaped domestication in South America, traveled north across the Great Plains, and eventually became wild mustangs.

The only problem is that the story is not true.

There are native Turtle Island horses, although they became endangered after contact with Europeans, their numbers were reduced to just four mares before they were saved by a group of Ojibwe men. Those horses, which lived in the boreal forest of Ontario and the upper Midwestern United States, are called Ojibwe spirit horses.

They are still in danger of extinction, with about 150 in existence today. Eight of these horses are housed at Mādahòkì Farm, a tourism and event destination managed by indigenous experienceswhere they are a living representation of the broader work of recovery, education and celebration of the indigenous cultures and traditions of the farm.

“You are never going to find a better example of reconciliation than those horses,” said Maggie Downer, cultural ambassador and organizer of the equine-assisted learning program at Mādahòki Farm. Canadian National Observer.

The farm is saving and recovering Ojibwe spirit horses, which Downer says were nearly extinct after colonization. Horses were never domesticated; they were considered pests by many settlers who would have had larger domesticated races, Downer says, and are part of a larger pre-contact history of Indigenous Peoples that was all but erased.

what people are reading

But now the horses are an active attraction for the farm and an iconic lesson in colonization history for indigenous and non-indigenous people alike.

The point is captured by the name Mādahòki, Anishinaabe for “sharing the land”. Its welcoming atmosphere speaks to the educational and cultural center that Mādahòki has become since it opened last October.

The farm came about after Trina Mather-Simard, director of Indigenous Experiences, heard about the story of Ojibwe spirit horses on the radio from artist Rhonda Snow.

Eight spirit horses live at Mādahòkì Farm, a tourism and events destination managed by Indigenous Experiences, where they are a living representation of the farm’s broader work of recovery, education and celebration of indigenous cultures and traditions.

Snow paints images of spirit horses, among other subjects, in the woodland style popularized by Norval Morrisseau and other Anishinaabe artists.

“She was talking about the Ojibwe spirit ponies, and it blew my mind,” he says. “I myself am Ojibwe and my daughters are horsemen, and I had never heard of them.”

After the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic passed, Mather-Simard and her daughters bought four of the horses.

It was the perfect time for Indigenous Experiences. The company had just lost its cultural space — a seasonal teepee village on Victoria Island, near downtown Ottawa — and moved to the Canadian Museum of History across the river in Quebec.

A space was opened in the green belt that was the perfect solution: 164 acres of land allowed the company to expand from cultural programming to a land-based educational model.

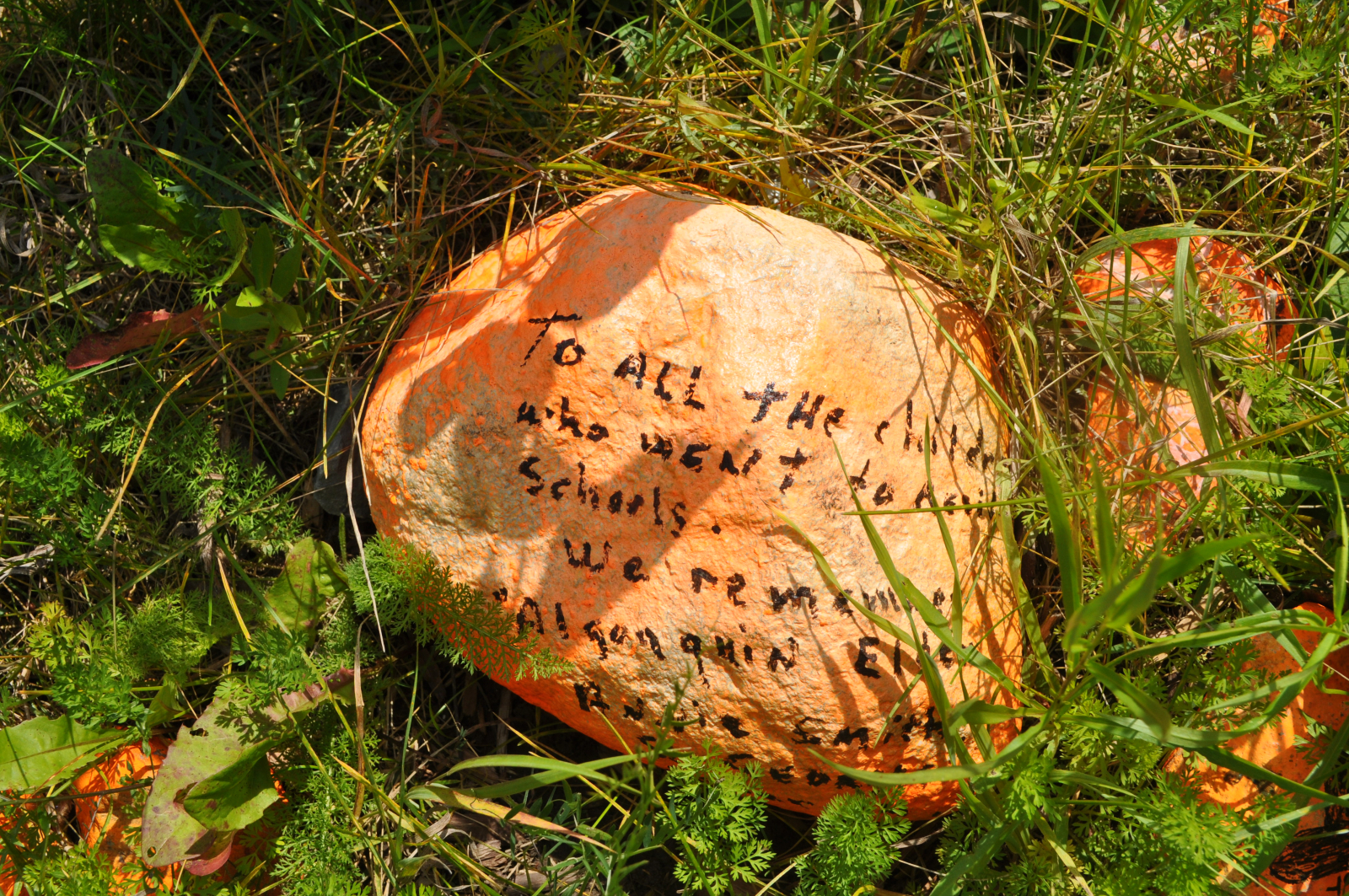

On the estate, there are garden beds filled with tobacco and Anishinaabe. Three sisters (beans, corn and squash grown in unison), in addition to a nature trail with information on native plant species and medicines and lined with reconciliation stones for visitors and the elderly.

The location also serves as a festival site. He organized an indigenous summer solstice festival on National Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21.

There’s also a shop stocked with the work of indigenous artists, artisans and chefs, including traditional indigenous foods like bison and char confit.

In the long term, Mather-Simard hopes to build fenced trails for Ojibwe spirit horses to simulate a wild habitat. The farm also hopes to create enclosures to house bison and caribou to provide a traditional food hub for indigenous people in the area.

Mādahòkì Farm hosts programming initiatives for indigenous communities and youth.

On August 15, the farm inaugurated indigenous food. It is an eight-week culinary training program for indigenous youth intended to teach professional culinary skills to those hoping to work in indigenous food services. Participants will learn about gathering, fishing, planting, and preparing and producing traditional foods.

The farm also has a Equine Assisted Learning (EAL) program run by Downer, who is a Haudenosaunee from Thayendanegea, and her assistant Charlotte Smith, a non-Indigenous equestrian. The program teaches boundaries and trust, and provides therapy to participants, but with a twist: its curriculum is indigenized to model the teachings of the Seven Anishinaabe Grandfathers and bring cultural sensitivity to indigenous participants. The farm has already worked with at-risk youth and Downer, who has a background in social services, hopes to expand that work.

Smith, who has worked in professional Western horsemanship all his life, says it’s a relief to learn a decolonized understanding of the art.

It is why the EAL Indigenized farm model is not goal-based, but instead focuses on healing and partnership.

“It’s about surrounding ourselves with a healthy life, that we all live in society,” says Downer.

“Today, we hear about the sacred circle. In the city, we sometimes forget that it is not just people who live in that circle: our animals, our wings [animals]including our plants, and seeing that whole picture, including our horses, not as tools to use, but as teachers.”

Matteo Cimellaro / Local Journalism Initiative / Canadian National Observer