This story was originally published by Grinding and appears here as part of the Climatic desk collaboration.

Why does it seem like the world has made so much progress in the fight against global warming, but also none at all?

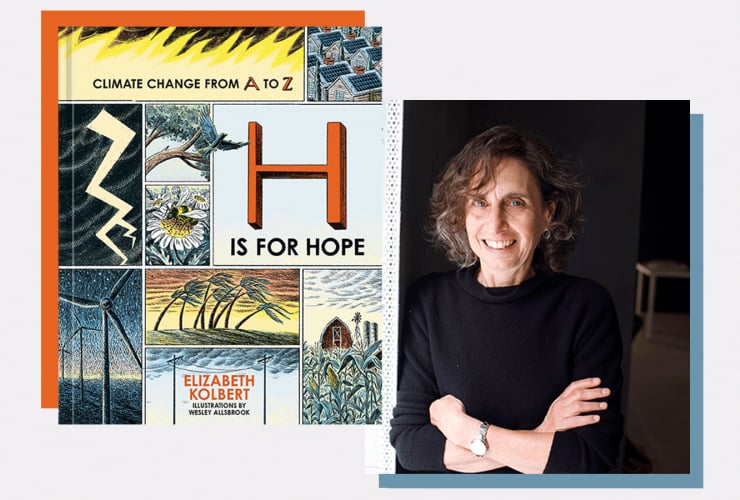

In H is for hope: climate change from A to Z, Elizabeth Kolbert, a long-time environmental journalist, considers tough questions like these. Using simple language, she explains that governments are passing climate-friendly laws, clean energy is expanding, companies are creating green technologies, and yet fossil fuel emissions are still rising, after all these years.

Kolbert’s latest book, an introduction illuminated by Wesley Allsbrook’s colorful illustrations, is a quick and entertaining read. Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish scientist who wanted to discover what caused ice ages, came up with the idea of carbon dioxide and built the world’s first climate model in 1894. Arrhenius imagined that a warmer world would be a warmer world. happy for humanity. . B is for “blah blah blah”, the climate activist Greta Thunberg’s mocking summary than three decades of global climate conferences have achieved. C is for capitalism, a compelling explanation for why those conferences didn’t accomplish much.

Kolbert, editor of The New YorkerHe has written several books, including The sixth extinction, a Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the asteroid-level power of Homo sapiens to wipe out other species. In H is for hope, bases the abstract problem of climate change on concrete experiences. Kolbert ends up riding a stationary bike in a humid 106 F vault, monitored for an experiment. (“What will the future we are creating really feel like?”). He looks at the blades of a 600-foot wind turbine off the coast of Rhode Island and, after visiting a “green concrete” company in Montreal, he takes home a cement block of the substance as a souvenir.

In an interview with Grinding, Kolbert explained why he believes climate change resists traditional narratives about hope and progress and how he attempted to tell a more complex and realistic story in his new book. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. I want to start by talking about hope, which is the way people usually end interviews. I’ve heard scientists and climate activists say they’re tired of being asked what gives them hope, I think because it can seem naive. How can we talk about hope in a way that is more realistic and helpful?

TO. Well, as you say, a lot of people have pointed out that that’s not really the opposition we should be focusing on, hope versus no hope. I think we should focus on action versus non-action. How we feel about it…it really doesn’t make much difference to the climate. what we do It’s what makes the difference. Now, having said that, after having written this book called H is for hopeI’m very interested in how we think about hope, and that’s one of the motivating ideas behind the book.

Q. How did you end up choosing that title? I think there’s something charming about a title that emphasizes optimism but also plays on Sue Grafton’s detective novels; you know, her book was H is for homicide.

@ElizKolbert wants us to rethink the stories we tell about climate change. #ElizabethKolbert #ClimateChange

TO. Good. There is also a really wonderful book by Helen Macdonald called H is for falcon. Then I knew I wanted to name the book after one of the letters; that’s the point, it’s an alphabet. And that turned out to be the obvious candidate.

Q. I thought that approach was interesting. What inspired you to write an alphabetical manual on climate change?

TO. I was trying to revive this story, which can be very overwhelming and has many different aspects. It’s really everything, everywhere, everything at once, and on one level, I was trying to break it down so that people would understand it and understand it in all its complexity. On the other hand, he was also trying to suggest that any simple narrative was probably incomplete.

Q. You started the book by saying that climate change resists narrative. What do you mean by that?

TO. It is not personified. It has no destination. You know, we all had a hand in causing it. We all participate in suffering it. Obviously, some participate much more than others in its cause and some suffer from it much more than others. It is this perpetual and progressive problem that will be with us forever. And when it’s serious, when there’s a crisis, a wildfire or a hurricane that’s made worse by climate change, it’s still not exactly caused due to climate change. You have that agency problem and stories demand agency.

Q. One of the themes of the book is the difficulty of considering climate change on a deeper level, the feeling that we are watching things fall apart but not really internalizing it, or that we are waiting for someone. or some miraculous technology to rescue us. Why do you think people have that response?

TO. On the one hand, it is a global problem. It has been described as the ultimate “tragedy of the commons” problem. It has to be addressed on a global scale. That’s why it’s very easy to feel overwhelmed. “What does it matter what I do?” On the other hand, I think what we’re seeing, in the United States in particular (I include myself in this), is that we are very stuck in our ways, which are very carbon intensive. So I think we would like every solution to be. keep proposing something that would allow us to continue doing exactly what we are doing, just in a different way. And that’s what we want to hear.

Q. That’s true. It’s really hard to imagine how we would live different lives, or what exactly those lives would be like. And I feel like that’s part of the problem.

TO. Yes, and our entire economy is based on doing things a certain way. You know, there’s a big argument in climate circles, which is one of the points of the book: Can you have what’s called “green growth?” Can you just keep growing, but do it in a quote-unquote “green” way or not? That is a question without an answer.

Q. How do you think we should change the narratives that are told about climate change?

TO. Well, this book is my attempt to do that. I can’t give you the example of climate change that is going to change everyone’s perceptions of it, or the story that is finally going to overcome all the nonsense. Many approaches have been taken, some more successful than others, but we still seem stuck. And I was really trying in this book to solve that problem, or play with that problem, that traditional narratives don’t seem to work.

Q. Was there anything else you wanted to say about the book?

TO. I think the important thing about climate change coverage is that it has some element of pleasure, which seems strange for such a grim topic. But I think what we, and I include artist Wesley Allsbrook, whose incredible illustrations are a big part of the book, tried to do was make it an enjoyable reading experience and a super visual experience. I think relentless sadness gets to people, and this book, while it definitely has a very serious message, tries to offer something in a fun way, I hope.